These days, it’s far more accurate to think of websites as online applications that execute a number of functions, rather than the static pages of old. Much of this robust functionality is due to widespread use of the JavaScript programming language. While JavaScript does allow websites to do some pretty cool stuff, it also presents new and unique vulnerabilities — with cross-site scripting (XSS) being one of the most significant threats.

Contents

Cross-site scripting, commonly referred to as XSS, occurs when hackers execute malicious JavaScript within a victim’s browser.

Unlike Remote Code Execution (RCE) attacks, the code is run within a user’s browser. Upon initial injection, the site typically isn’t fully controlled by the attacker. Instead, the bad actor attaches their malicious code on top of a legitimate website, essentially tricking browsers into executing their malware whenever the site is loaded.

JavaScript is a programming language which runs on web pages inside your browser. This client-side code adds functionality and interactivity to the web page, and is used extensively on all major applications and CMS platforms.

Unlike server-side languages such as PHP, JavaScript code inside your browser cannot impact the website for other visitors. It is sandboxed to your own navigator and can only perform actions within your browser window.

While JavaScript is client side and does not run on the server, it can be used to interact with the server by performing background requests. Attackers can use these background requests to add unwanted spam content to a web page without refreshing it, gather analytics about the client’s browser, or perform actions asynchronously.

When attackers inject their own code into a web page, typically accomplished by exploiting a vulnerability on the website’s software, they can then inject their own script, which is executed by the victim’s browser.

Since the JavaScript runs on the victim’s browser page, sensitive details about the authenticated user can be stolen from the session, essentially allowing a bad actor to target site administrators and completely compromise a website.

Another popular use of cross-site scripting attacks are when the vulnerability is available on most publicly available pages of a website. In this case, attackers can inject their code to target the visitors of the website by adding their own ads, phishing prompts, or other malicious content.

Now that we’ve covered the basics, let’s dive a little deeper. Depending on their goals, bad actors can use cross-site scripting in a number of different ways. Let’s look at some of the most common types and examples of XSS attacks.

Stored cross-site scripting attacks occur when attackers store their payload on a compromised server, causing the website to deliver malicious code to other visitors.

Since this method only requires an initial action from the attacker and can compromise many visitors afterwards, this is the most dangerous and most commonly employed type of cross-site scripting.

Reflected cross-site scripting attacks occur when the payload is stored in the data sent from the browser to the server. These attacks are popular in phishing and social engineering attempts because vulnerable websites provide attackers with an endless supply of legitimate-looking websites they can use for attacks.

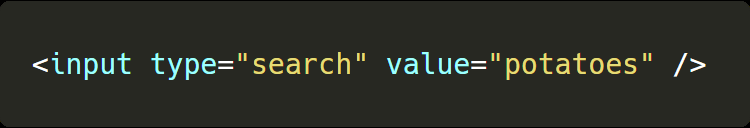

A typical example of reflected cross-site scripting is a search form, where visitors sends their search query to the server, and only they see the result.

Attackers typically send victims custom links that direct unsuspecting users toward a vulnerable page. From this page, they often employ a variety of methods to trigger their proof of concept.

Self cross-site scripting occurs when attackers exploit a vulnerability that requires extremely specific context and manual changes. The only one who can be a victim is yourself.

These specific changes can include things like cookie values or setting your own information to a payload.

Note

An example of self cross-site scripting include running unverified code on social media platforms or online gaming where some reward or information is offered by running the code.

Blind cross-site scripting attacks occur when an attacker can’t see the result of an attack. In these attacks, the vulnerability commonly lies on a page where only authorized users can access.

This method requires more preparation to successfully launch an attack; if the payload fails, the attacker won’t be notified.

To increase the success rate of these attacks, hackers will often use polyglots, which are designed to work into many different scenarios, such as in an attribute, as plain text, or in a script tag.

DOM-based cross-site scripting attacks occur when the server itself isn’t the one vulnerable to XSS, but rather the JavaScript on the page is.

As JavaScript is used to add interactivity to the page, arguments in the URL can be used to modify the page after it has been loaded. By modifying the DOM when it doesn’t sanitize the values derived from the user, attackers can add malicious code to a page.

Note

An example of DOM-based cross-site scripting attack would be when the website changes the language selection from the default one to one provided in the URL

Attackers leverage a variety of methods to exploit website vulnerabilities. As a result, there is no single strategy to mitigate the risk of a cross-site scripting attack.

The concept of cross-site scripting relies on unsafe user input being directly rendered onto a web page. If user inputs are properly sanitized, cross-site scripting attacks would be impossible. There are multiple ways to ensure that user inputs can not be escaped on your websites.

To protect your website from XSS attacks, we encourage you to harden your web applications with the following protective measures.

Restrict user input to a specific allowlist. This practice ensures that only known and safe values are sent to the server. Restricting user input only works if you know what data you will receive, such as the content of a drop-down menu, and is not practical for custom user content.

While HTML might be needed for rich content, it should be limited to trusted users. If you do allow styling and formatting on an input, you should consider using alternative ways to generate the content such as Markdown.

Finally, if you do use HTML, make sure to sanitize it by using a robust sanitizer such as DOMPurify to remove all unsafe code.

When you are using user-generated content to a page, ensure it won’t result in HTML content by replacing unsafe characters with their respective entities. Entities have the same appearance as a regular character, but can’t be used to generate HTML.

Session cookies are a mechanism that allows a website to recognize a user between requests, and attackers frequently steal admin sessions by exfiltrating their cookies. Once a cookie has been stolen, attackers can then log in to their account without credentials or authorized access.

Use HTTPOnly cookies to prevent JavaScript from reading the content of the cookie, making it harder for an attacker to steal the session.

Note

This method only prevents attackers from reading the cookie. Attackers can still use the active browser session to send requests while acting as an admin user. This method is also useful only when relying on cookies as the main identification mechanism.

Our Website Application Firewall (WAF) stops bad actors, speeds up load times, and increases your website availability.

In the event of a cross-site scripting attack, there are a number of steps you can take to fix your website.

The first step in recovering from cross-site scripting is to identify where the vulnerability is located. You can refer to our helpful hacked website guide for detailed steps.

Once you have obtained information about the location of the malware, remove any malicious content or bad data from your database and restore it to a clean state. You’ll also want to check the rest of your website and file systems for backdoors.

Vulnerabilities in databases, applications, and third-party components are frequently exploited by hackers. Once you have identified the vulnerable software, apply patches and updates to the vulnerable code along with any other out-of-date components.

When a compromise occurs, it is important to change all of your passwords and application secrets as soon as the vulnerability is patched. Prevent reinfection by cleaning up your data to ensure that there are no rogue admin users or backdoors present in the database.

Consider setting up a web application firewall to filter malicious requests to your website. These can be particularly useful to provide protection against new vulnerabilities before patches are made available.

If you believe your website has been impacted by a cross-site scripting attack and need help, our website malware removal and protection services can repair and restore your hacked website.

Our dedicated incident response team and website firewall can safely remove malicious code from your website file systems and database, restoring it completely to its original state.

Cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks occur when hackers execute malicious code within a victim's browser. The bad actor attaches their code on top of a legitimate website. This tricks browsers into loading malware whenever the site loads.

There is no single strategy to prevent a cross-site scripting attack. Several protective measures are necessary to protect your website from XSS attacks. These include allowlisting values, restricting HTML in inputs, and using a web application firewall (WAF).

The best way to detect cross-site scripting on your site is to use a malware scanner. One free option is Sucuri’s SiteCheck. Once detected, you will need to locate and remove any malicious code and patch the vulnerability. This will prevent any further cross-site scripting attacks.

To protect your website against cross-site scripting, you must harden any web applications. This includes allowlisting values, restricting HTML in user inputs, adding HTTPOnly tags to cookies, and using a web application firewall (WAF).

Say on top emerging website security threats with our helpful guides, email, courses, and blog content.